-

Courses

Courses

Choosing a course is one of the most important decisions you'll ever make! View our courses and see what our students and lecturers have to say about the courses you are interested in at the links below.

-

University Life

University Life

Each year more than 4,000 choose University of Galway as their University of choice. Find out what life at University of Galway is all about here.

-

About University of Galway

About University of Galway

Since 1845, University of Galway has been sharing the highest quality teaching and research with Ireland and the world. Find out what makes our University so special – from our distinguished history to the latest news and campus developments.

-

Colleges & Schools

Colleges & Schools

University of Galway has earned international recognition as a research-led university with a commitment to top quality teaching across a range of key areas of expertise.

-

Research & Innovation

Research & Innovation

University of Galway’s vibrant research community take on some of the most pressing challenges of our times.

-

Business & Industry

Guiding Breakthrough Research at University of Galway

We explore and facilitate commercial opportunities for the research community at University of Galway, as well as facilitating industry partnership.

-

Alumni & Friends

Alumni & Friends

There are 128,000 University of Galway alumni worldwide. Stay connected to your alumni community! Join our social networks and update your details online.

-

Community Engagement

Community Engagement

At University of Galway, we believe that the best learning takes place when you apply what you learn in a real world context. That's why many of our courses include work placements or community projects.

News

Likely cradle of new planet discovered

We have now discovered thousands of planets around other stars. In fact it is pretty likely that any start one might see on the night sky has some planets orbiting around it. What we have learned from these discoveries in the past decades is that planet formation is efficient, it happens a lot! But we also learned that it must be a very complex process, because we get many different planetary systems as the end products. In some massive gas giants orbit their host star in a matter of days, in other we have tightly packed systems of massive rocky planets (so-called Super Earths) which are aligned in beautiful mathematical resonance with each other. However, among the several thousand planetary systems out there, we have not yet found a twin of the solar system.

To understand why we get this diverse set of planetary systems, and ultimately what it takes to make something similar to our own solar system we are rewinding the clock and look at the very youngest systems of planets that are still in formation. To be more precise, we are looking at the dust and gas rich disks surrounding young stars in which these future planets are being born at this very moment.

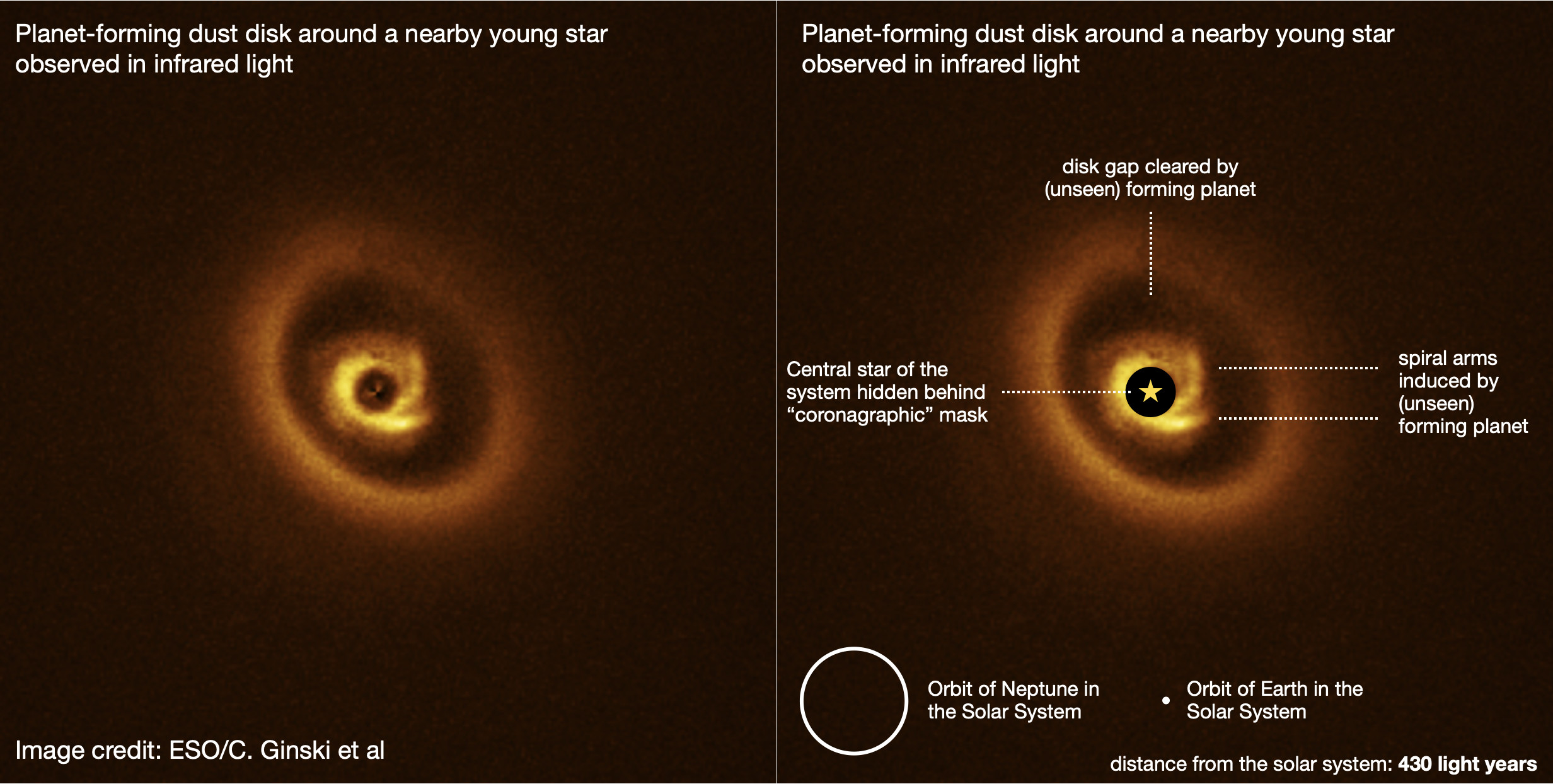

Using the European Southern Observatories "Very Large Telescope" in Chile we have recently taken an image of the disk surrounding the star (with the somewhat unwieldy name) 2MASSJ16120668-3010270. This disk, seen in the image below, shows all the hallmarks of a site of current planet formation. In particular the combination of the outer ring and inner spiral structures is something that is predicted by planet-disk interaction theory.

The image above shows an annotated version of the disk surrounding the 2MASSJ16120668-3010270 system. We see that there are multiple structures in the disk, such as an outer ring, a gap and small spiral arms in the inner part of the disk.

Based on the features in the disk that we see, we think that there is a massive gas giant forming in this disk. Because in astronomical terms it must have formed fairly recently (give or take a million years), the planet will still be very hot and it should be possible to spot it in infrared light. We have secured time on James Webb Space Telescope to do just that. Our observations should be carried out within the next few months and hopefully we will be able to show an image of this new baby planet soon.

With all of these discoveries it is always important to understand that science and in particular modern observational astronomy is very much a team sport. This particular study included an international team of colleagues from 9 different countries. Amazingly it also included several of our very own University of Galway graduate students! Without these bright young researchers we would not have been able to make this discovery. So a huge thanks to Chloe Lawlor, Jake Byrne and Dan McLachlan who are all co-authors of this new article.

The team of graduate students in the Galway Planet Formation Group that were closely involved in the preparation of the journal article on the 2MASSJ16120668-3010270 system. From left to right: Chloe Lawlor (PhD student), Jake Byrne (MSc student), Dan McLachlan (MSc student).

Click HERE for the open access research article or HERE for the related ESO picture of the week.